An Education

Steven Spurrier never stopped learning

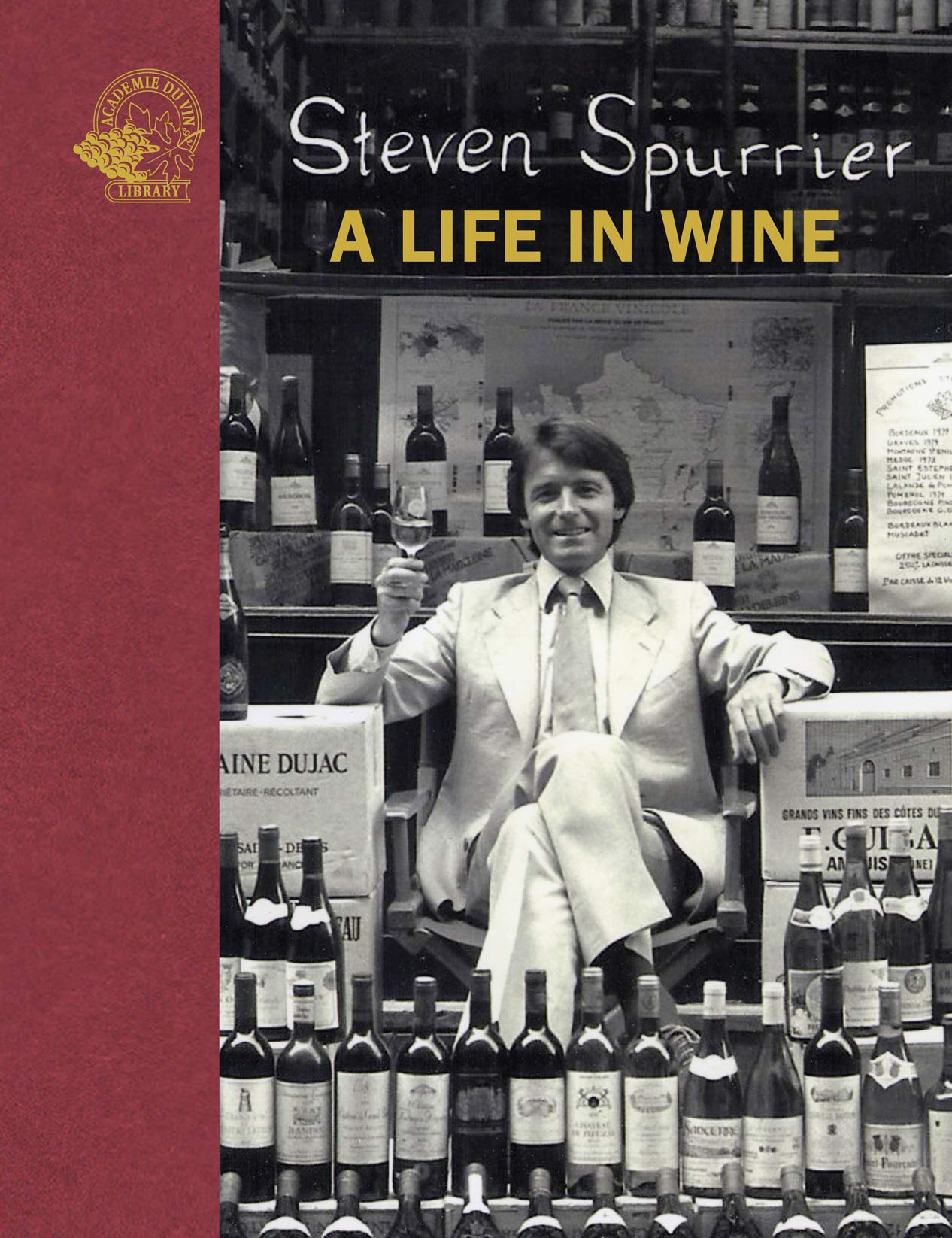

Steven Spurrier, who has been called “the man who changed wine forever” thanks to his role in organizing the momentous Judgment of Paris tasting, died March 9 at home surrounded by his family. He was 79.

One year ago, Spurrier spent a week in Toronto to promote the launch of the revitalized Academie du Vin wine school in Canada and a related publishing initiative, the Academie du Vin Library. On March 13, as the province was preparing to shut down to slow the spread of COVID-19, I interviewed Spurrier in the lobby bar of the St. Regis hotel prior to attending a special reception in his honour at The Vintage Conservatory in Yorkville. Edited for clarity, this is a transcription of our conversation about wine and its appreciation.

I wanted to talk to you about wine education in general. Your career trajectories have taken many different paths, but the one through line it seems to me is education.

I consider myself more a communicator than an educator. But that’s not strictly true, because L’Academie du Vin was the first private wine school in France. And we did educate people, the sell point was people wanted to do wine courses, so we created Tour de France as our first course. And, then we did advanced courses, and so on and so forth. I’ve personally been in the wind education business, most of my life, and writing about it, and Decanter (magazine). But I view myself as more as a communication than an educator per se. I didn’t wear the professorial hat; I wear the ambassadorial hat.

What is interesting because what Marc (Nadeau) is starting off [the Academie du Vin wine school in Canada]. This course has been created based on a book I wrote back in the mid-1980s. You absolutely have to have the basic notes. I think you'll find yourself back at school, you were told what books to read. You need the background, you need the building blocks and the person giving the wine course could communicate in an enthusiastic and knowledgeable way, and associate and instill the desire to learn and to learn more. I was very well taught at school by certain masters. And the most important thing I think about children at school is they should have the wish to learn. If the schools turn them off that then they've done a very bad job. Once you have the wish to learn, then off you go.

That 1983 book helped opened my eyes. Your book and Michael Broadbent’s wine tasting book were among the first things that I checked out at the library to learn more about wine.

Academie du Vin Complete Wine Course was the first of its kind. And then came Jancis Robinson, then, most importantly, Michael Schuster. But this book, sold 150,000 copies in six hours. This wouldn’t happen today. But it was a great success, because it laid it out very clearly. What was a real first is that is all the photographs of the wine colours were actual wines. They were photographed by a professional photographer. He said, in previous books, the colors have been made up. But these were actual wines. It took three days and a lot of photographs and a lot of corks pulled.

I wrote about four or five books in between 1982 and 1986. The Academie du Vin Wine Course is what had the most influence. But the book I like most was the Academie du Vin Guide to French Wines, which combined my French Country Wines and French Fine Wines, both kind of pocketbook sized volumes into an overall coverage of French wines. In 1984-85, it could not have been surpassed. It was very, very good. I was very pleased to have written those books.

I thought of taking the Master of Wine exams. The institute asked, "Well, have you done the WSET Diploma?" I said, "No, of course not." They said, "Well, we'll allow you to take the MW because all of your books are MW reference books. And then they send the exam papers, and I took one look at those and said "No, no, no.... Not for me!"

A challenge I find as educator is discussing the reference points. I sometimes feel like coming into the world of wine in 1988, as I did, was the last point in time some of these benchmark wines were accessible. They were a reach, but you could at least put your hands on them. Whereas now, so many benchmarks are unicorns that students can only read or dream about.

Michael Schuster, whose book, Understanding Wine has really taken the Academie du Vin Wine Course to the nth degree, is very, very close friend of mine. He is a top educator of potential MW students in London. He said in the last five years, maybe one out of his seven to 16 students has actually drunk a First Growth. They don’t have the experience. They might have tasted it in en premier tasting, but they wouldn’t have sat down at lunch and drunk a First Growth.

And there is a world of difference between interacting with an ounce of wine at tasting and writing a note compared to actually having the pleasure of experiencing the first and last sip of a bottle over time...

Wines have never been better made all over the world. And therefore, New World wines, which were dismissed 30 years ago adjust for other wines. I mean, the Argentinian malbecs are a better expression of malbec than a malbec from Cahors. Some of the Australian shirazes will rival those from the northern Rhône. I think that for the wine consumer or the person wanting to know about wine it’s all there… Absolutely, it’s all there’s and there’s much more there in accessible terms than ever before. So maybe the super benchmarks have gone out of sight price wise, but the variety of wine to increase your education and knowledge is much bigger.

On the subject of benchmarking, if you’ll forgive me for asking about 1976, as it is probably the thing that you probably talked to at length and there’s no new ways in. But I think my regret about those sorts of tastings, which have been staged seemingly everywhere in the wake of the Paris tasting, has made wine into some sort of Olympic kind of competition. As opposed to a benchmarking exercise of looking at the range of quality wines in the tasting, the results are often reduced to which producer ranked first, second or third.

I think the Parker point system, the 100-point scale, made wine more on Olympic competition more than the Judgment of Paris. The important thing that the Judgment of Paris did, which had not been done before, was to create a template whereby unknown wines of quality could be tasted blind against known wines of quality. And if the judges were themselves of quality, the opinion of the judges would be respected. And that really did open the gates; it opened the playing field.

It’s been exaggerated, but I don’t think too much. Look at Eduardo Chadwick and the Berlin tasting in 2004, there were 14 wines. He was showing his wines to get recognition. And I was sitting next to him on the top table... And when the results were read out from the 10th wine upwards, he got equal force with Margaux, and he relaxed and smiled. He switched off. He wasn’t paying attention when Wine Number Three was Lafite and Wines Number Two and One were his wines. He just looked completely stunned because he thought they were down in the last four (finishing out of the Top 10). He took that all over the world, which did a large amount for Eduardo Chadwick and Errazuriz, but ultimately did more for Chilean wine as a whole. We did The Judgment of Paris in 1976 and did it again in 2006. The results were confirmed very strongly. But Eduardo took his tastings around the world for years to confirm results. It wasn't a flash in the pan.

If you're a little bit behind geographically, being as isolated as Chile is, you need to bang the drum...

Yes, you need to wave the flag. This is the advantage of Australia and New Zealand in England is they have cricket teams. And New Zealand has the All Blacks rugby team. Sports represent a country much more than anything else. People can identify with a country immediately through sports. Countries need an identity and Chile didn't really have it.

Any final thoughts?

One of the great advantages of modern winemaking is wines are much more drinkable, much younger than they were in the past. But then the disadvantage is that nine people out of 10 don’t consume older, mature wines. Therefore, they cannot sense the character. Tasting a wine which is showing its age but has still kept its character is very educational. Hugh Johnson made the absolute spot-on remark as usual, when he said he used buy cases of 12 bottles until quite recently: “You drink the first three bottles before they’re at their best. You then consume the next six bottles on the plateau, maybe over 10 years or so when they were showing how you expected them to show for full satisfaction. And then you drink the last three bottles in their decline. remembering how good they were.” You win on all points. I guess the first three, you can see how good they're going to become. The last three you remember how good they were!

STEVEN SPURRIER, A Life in Wine, was published by Academie du Vin Library in 2020.